Out of the Camp Ch. 16 – Reinvention

The bank weren’t too impressed with our filching the £3,500 profit from the Macduff house to give to the families of our new employees in the North Sea. Of course, the manager was quite correct in pointing out that we ought to have consulted them first since we had agreed that that money would be our deposit on the new house in Peterhead after the loan had been approved. I actually asked him if he would have agreed to our “borrowing” the money if we had approached him first, and he said the decision wasn’t his to make but that the property division would have had to be consulted. He responded to my grin saying, “Yes, they’d have turned it down initially, but I would have pressed your case in light of the fact that substantial moneys are owed to you from a Haliburton company (Brown & Root) and that you expected payment within 4-6 weeks.” He understood our concern and forgave us despite the cashflow problems we were having with the antenna manufacturing business. Thankfully, the domestic and marine service side was going well but the problem there was that my time was being impossibly stretched and people were having to wait longer for appointments than had been the case in the past. If I’d had any local competition at the time, I’d have been in big trouble.

It took almost seven weeks and many sleepless nights, but Brown & Root finally paid up and we were able to finalize employment contracts for our new employees, and sign B&R’s standard subcontract agreement which included their mandatory offshore and subrogation protection clauses. Offshore employment insurances were also set up which covered our employees and ourselves for most foreseeable eventualities. Since all of the dominos had obligingly, eventually fallen into place, we were now also able to close on our new Peterhead house, thereby bringing to an end my daily 100 km round trip commute to work and back. I’d miss living in MacDuff, of course, as it’s a peaceful, pretty little town on the Moray Forth with wonderful, big hearted people, but there was a consolation in that I’d continue to visit occasionally as we were hanging on to our remarkably accommodating bank manager there.

The Seahawks were selling like hotcakes; we were sending them all over the country, not only to vessel owners but a number of independent marine electronics sales & service companies. Our biggest customer was Electronics Marine in Hull who were ordering ten at a time and selling them as fast as we could fill orders. Also, a subsidiary of Marconi Marine, Coastal Radio in Colchester were placing repeat orders for five. We had several units out on evaluation with a number of marine electronics companies in Europe. We’d enrolled in the UK Government’s ‘Exports Credit Guarantee Department’, which was an insurance programme designed to protect small and medium sized businesses from risk and to help smooth the path of their international expansion. Letters of Credit were another method by which we’d provide ourselves with some protection, but they only had a limited ‘shelf-life’ and weren’t ideal. In anticipation of sales continuing at this level, or even increasing, I had taken the part timer, Oscar, on as a full-time employee to expedite our production output. This worked well for some considerable time though I did notice the stacks of electronics magazines “growing like Topsy”, and no evidence of either of the techs responding to my request that when things were quiet, they take a walk down to the harbor to do some canvassing for sales or service work on the fishing boats.

The B&R contract was continuing to run smoothly, the clients were satisfied, the men and their families were happy, particularly so as this contract was expected to run for a minimum of three years. Approximately nine months into the contract we received an enquiry from McDermott International, another huge multinational offshore construction conglomerate. It seems that Phil of Jackson Marine had been speaking to his opposite number at McDermott who’d told him about some upcoming pipelaying contracts. They had been discussing refits and equipment winter maintenance of the radio rooms on two of their barges that would be leaving the Kanaaldok in Antwerp and heading for the southern North Sea. The McDermott comms director, Graham, asked Phil about radio operators for the barges as he knew about Phil’s prior side business and Phil explained what had transpired and his having to give it up, so passed on our number, hence the call which had actually come from the operations center in their European Corporate office in Brussels. The vessels concerned were the Jet Barge 4 and the Lay Barge 27. Basically, the former creates a trench on the seabed and the latter follows along laying pipe along the trench. Looking at future potential prospects of what was fast becoming a specialist technical personnel contracting operation, I had some difficult decisions to consider regarding my other business activities. However, the potential income and profitability in the new operation made the decision much easier especially taking into account the size of the market and future North Sea projected activity continuing well beyond 2000.

I approached the man who’d given me my first break in the North East and explained my dilemma. He knew, of course, about the other developments and also that it was taking me longer to get to their customer’s installations. I explained that I was unable to carry on with the domestic antenna business and suggested that I pass it on, with his permission, to the closest alternative installer, in Buckie. He was extremely understanding and, as a businessman, was fully supportive of my decision. I didn’t mention just how much help and support outside of the business he and his wife had actually given me. In the very early days, they regularly would invite me to their home for dinner and we had become real friends and, in fact, we’re still in touch to this day.

The other troubling issue was the ‘Seahawk’ antenna manufacturing operation. This was much more complicated and would take some unravelling. The overdraft had become a running sore with the bank and relations there were very strained. The extended credit agreement with the family friend’s manufacturing company had been lengthened but it was becoming clear that the business wasn’t anywhere near breaking even. I wasn’t getting any help from the two ex-RAF techs who were making the antennas. They just refused to do anything but assemble the antennas and repair any faulty units brought in by customers, in addition to other electronic equipment. Their position was that they were employed to assemble the antennas and carry out repairs on customers’ equipment, not wander around the harbor looking for business. I tried to explain that small business is not like the Royal Air Force, you have to be flexible and take on additional roles to make things work. It was also, of course, about salaries but how could I give them an increase when we were losing money. In hindsight, of course, a cost analysis conducted up front providing cost per unit produced probably would have revealed that having two electronic technicians employed in what, in reality, was a simple assembly role, was never going to be cost effective.

I approached our largest customer Electronics Marine in Hull who had a small subsidiary operation making a marine distress beacon and an amateur VHF marine radio, which made me think that our antenna would fit perfectly into their product line. I asked if they might be interested in taking over our Seahawk manufacturing operation. We were about £13,000 in the red – which was a lot back then! – and I proposed that we would hand over all outstanding orders, current stocks, spare parts and all other materials, and also transfer the patent and trade-mark registrations to their company in exchange for taking on the debt. I also promised to provide client lists and contact information, agreed to introduce them to the plastics manufacturer in the hope that he would continue to make the casings. They agreed in principle to my proposal provided that all the information was accurate and also that they could reach agreement over the plastic casings. What, in fact, ultimately happened was that I met the plastics guy in Manchester, and we drove across to Hull together to meet and discuss the final agreement which, thankfully, eventually all worked out.

So, in one fell swoop – actually, in truth, the entire withdrawal operation, all two of them! took close to eighteen months to effect – I’d managed to extricate myself from two progressively more complicating situations, one that while successful, was very limited in its growth potential and the other, while losing money hand over fist, had great potential but was in dire need of fundamental restructuring and additional investment. The two technicians were shocked and angry when I announced my plan to dispose of the business and, I took no pleasure in pointing out to them that it needn’t have happened had they been more flexible and willing to assist in drumming up some business in the fishing community when they weren’t busy. Did I mention that Peterhead was then, and is to this day, the biggest fishing port in the UK. It was pretty clear that the ship’s antenna venture had become intractable, but in case you’re thinking it was a bit rash to also ditch the aerial installation business when it was so successful, and instead focus my energies on a speculative new venture in an industry that I had little or no experience in, you might have a point. But we’d taken a huge gamble in the first place in leaving London and coming to an area of the country I was unfamiliar with. In fact, I’d only been to Aberdeen once in my life and that was a few years earlier when ‘Listen’ had played a gig at the University of Aberdeen’s Student Union.

The point is that I could have, with some perseverance, have done the aerial thing in London; the reason for coming to the North East was to take advantage of opportunities in the burgeoning Offshore Oil Industry and we’d had a taste of it, could see the potential and felt that it was worth a further calculated risk. In fact, I still had Mary focused on the new offshore personnel venture. While I was engrossed in the various challenges at home, she’d actually made a PR trip to McDermott’s European office in Brussels after we’d been awarded the radio operator contract for the two McDermott barges, and the first four men had gone to Antwerp to meet the vessels before departure. The guy she met said that there’d be additional requirements later in the season when an additional barge, and possibly two would be mobilizing. In addition to this I had been canvassing drilling companies in Aberdeen and had some very positive feedback about potential future business opportunities in that area. I’d also been asked if we could supply medics and I answered in the affirmative with my fingers firmly crossed. I’d figure that one out later!

Images.

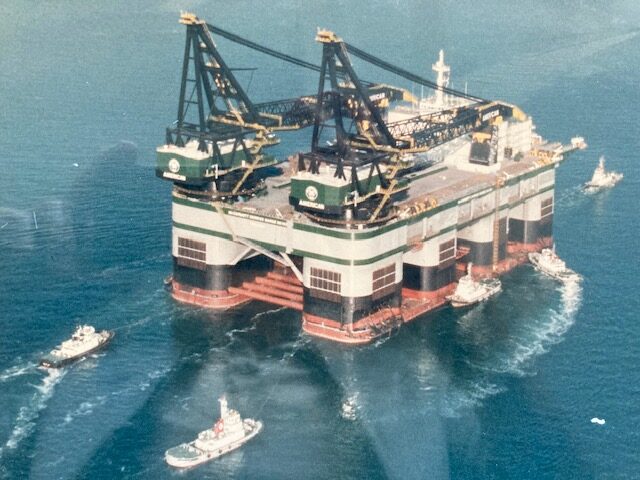

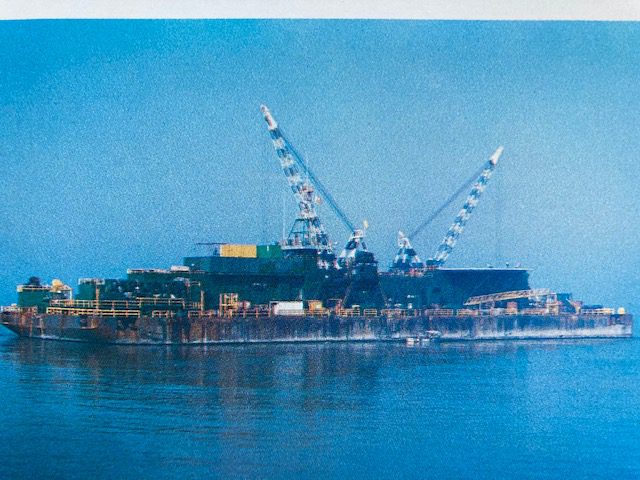

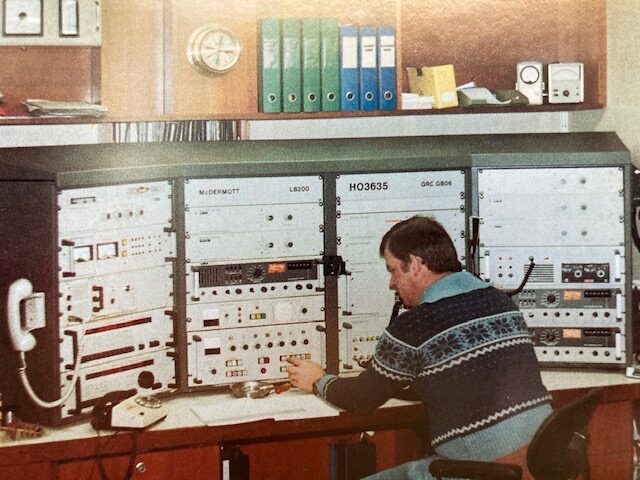

(1) McDermott Derrick Barge 101. (2) McDermott LayBarge 028 on location in Morecambe Bay, England in the in the Spring of 1982 prior to laying the British Gas pipeline from the gas field to the land-fall at Barrow-in-Furness. (3) A ‘Radioman’ at work in the radioroom on the McDermott Derrick Barge 100 in the North Sea. (4) A ‘Radioman’ operator at work in the Lay Barge 200 Radioroom designed installed and commissioned by Radioman Technical Services (RTS).