Out of the Camp Ch. 27 – Liberton and the Mines

So, then I started at Liberton Secondary and I really don’t remember anything about the first day or days or, indeed, anything much at all about my time there. My initial, overall feeling about being there was relief and real happiness but probably for all the wrong reasons. There was no bullying, and I made some good friends within a very short space of time and, sadly, this led to a lot of goofing off in classes. I’ve tried very hard to remember events at the school, teacher’s names, other class-mates’ names but the vast majority totally escape me. Peter Black was a pal and also James Smith, who was a neighbor. It was his Mum who sucked the wasp sting out of my eyebrow years before when we were wee. Fraser MacKay was another class mate and he shows up here on FB from time to time telling stories, and sharing antique pics of Embra. I do remember one time Mr. Platt, a soft-spoken young maths teacher standing helpless with a look of incredulity on his face as his 4th-year class disintegrated into absolute chaos, and he seemed utterly at a loss over how to stop it.

More optimistically, the music master, a short, wiry, grey-haired elderly man who always wore a black, sweeping master’s gown took no nonsense from anyone. It was the last day of term and, contrary to his better judgement, he had invited each member of the class to bring in their favorite record to play. As each class member came forward to play his or her offering, most often a current 45rpm chart hit, the master – I don’t remember his name – made suitably derogatory comments about the lack of musicality or the absence of any redeeming feature of each piece in a good-natured, teasing sort of way, and he was clearly enjoying himself. One boy, his name was Neil and who lived on the Gilmerton Road in what was to me a big house, and who I later learned played the piano, put on a track from a long-playing 33rpm album by Thelonious Monk. Of course, no one in the class had ever heard of him and the piece didn’t go down too well to say the least, as it wasn’t really what you’d call accessible jazz, far less, pop music! The master for his part, just nodded sagely not uttering a word. The grand finale so to speak, came when someone put on the song that was number one in the charts at the time, ‘Blue Moon’ by The Marcels. The master sat with a look of horror on his face and finally, when he could take no more, stood up and announced as much while sweeping out of the classroom, cape flying behind him while he announced with mock disgust over his shoulder, “You’re dismissed! Have a nice holiday!” And the entire class erupted in uproarious peals of laughter and vacated the classroom in his wake.

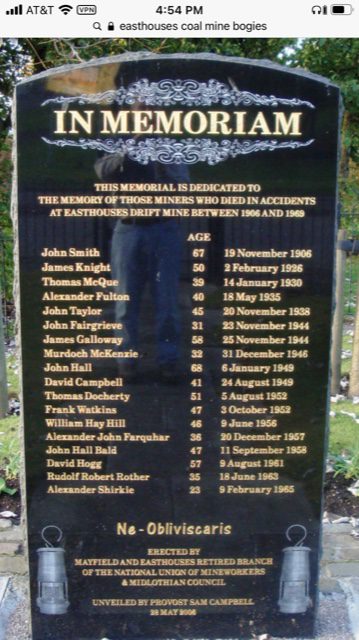

I don’t even remember my last day at Liberton or receiving the news that since I’d only managed to achieve two ‘O’- levels (English & Metalwork), I’d be required to leave. And leave I did, much to my Mum’s delight and much in line with family coal-mining tradition on both sides, my paternal grandfather having been killed at Dalkeith Colliery in an underground incident in 1918 when “a large stone fell upon him, and he was injured and died on 15th August 1918“, to quote the Procurator-Fiscal Statement dated 4th September, 1918. My father was three at the time. My maternal grandfather, on the other hand, was luckier as he lived longer. However, his was far from an easy life. In 1908 aged 14, he left school and went to work in the local pit, Manton Colliery in Worksop, Nottinghamshire. In 1913 as war was approaching, he was called up (conscripted) and joined the army, serving in Northern France. He was engaged in the Battle of the Frontiers on the French-Belgian border where, in 1915, he was shot in the spine and repatriated to the UK. Treated at the military hospital in Aldershot, he was eventually discharged and sent home to recuperate where, following his recovery, he went back to the colliery as a disabled veteran and served as a colliery lamp-man and, as such he had the responsibility for maintaining lamps and for issuing them from the lamp room at the start of a shift. He died in 1956 when I was ten and my recollections of him were, frankly, grim. I don’t remember how old I was when I last saw him, probably around 6 or 7, but I don’t remember ever seeing him smile, far less, laugh. I rather suspect his last years were hellish, probably stuck in that wheelchair wracked with pain and precious little relief. As a little boy, I thought he hated me because whenever we visited, it seemed to me he always stared at me and never smiled, ever! When it came to the relatives in England, I was always spoiled just because they saw me so seldomly and for such a short time and I guess I felt entitled to it.

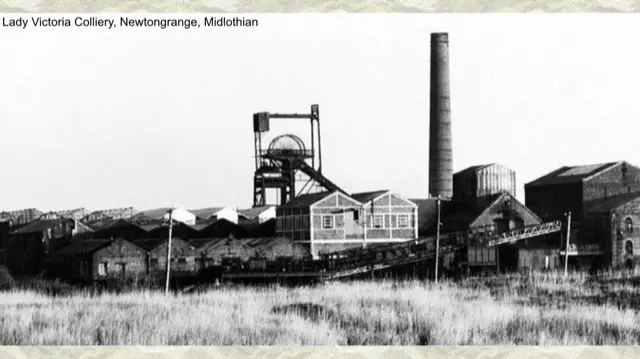

But I digress; so, in having passed the entrance exam, I joined the National Coal Board on a 5-year indentured apprenticeship (Yes! Indentured! More later.) in mechanical engineering. I started work at Newtongrange, Lady Victoria Colliery Central Workshops which was an engineering center for both, the Lady Victoria Colliery in addition to other pits in the Midlothian Mining area. The main workshop area was a huge aircraft hangar-sized engineering factory. There were giant, steam jack-hammers, huge lathes, drills, furnaces and anvils and many other machines performing every engineering function you can imagine. There was a classroom in the building where the apprentices would congregate from time to time for formal classroom engineering sessions, and separate classes in mining theory on day-release were held once a week in a nearby hut and tutored by a former mining engineer called Mr. Mabon, who had injured (or perhaps, lost) a leg in an underground accident years earlier. After all these years I don’t remember very much at all what we were taught but I do remember it was a really efficient system that took in about 30-35 new apprentices every six months and sent them off to nearby mines at the end of their initial training period. Most of the time during that period was spent in the workshops, and apprentices were assigned a department for about a month and then they’d be moved around so they each had some exposure to many of the activities that took place in the center. So, for example, one might start in the blacksmith shop and then be transferred to joinery, then heavy engineering, and so on until your six months were up. One thing that went on constantly was the teasing of new apprentices by the tradesmen at the workshops. There were constant pranks being inflicted on us naïve kids who thought we knew stuff. Of course, there was the old chestnut where, say, Sandy in the engineering maintenance shed would call you over and send you, for example, to the blacksmith’s shop to ask Big Bill for a long stand. Then, surprisingly, Bill the blacksmith would tell you to “wait right there” and he’d be right back. Well, of course, he didn’t come back and eventually it would suddenly dawn on you why all the guys in the blacksmith’s shop had smirks on their faces. You’d asked for a long stand and that’s precisely what you’d had by the time you realized that you’d really been had. Another topic that prompted teasing, particularly at the start of the week on a Monday morning was, football results. Pretty well everyone knew who everyone else supported and so, when any particular team had a received a thrashing from the opposing side, their life was made a misery for most of the day. Monday mornings also saw us apprentices reliving the latest episode of “Round the Horne”, a hilarious, hugely popular radio comedy program that was broadcast on a Sunday. Those Brits, old enough to remember such figures as Kenneth Horne, Kenneth Williams, Hugh Paddick and Betty Marsden will remember just how popular this show was. Every week we’d dissect each of the sketches, item by item, reliving the funniest moments and laughing at the same jokes all over again.

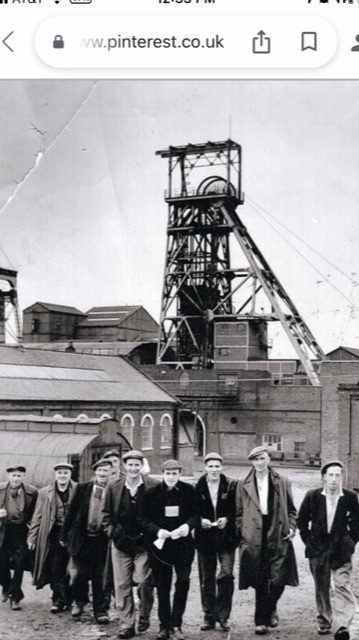

At the end of my 6 months initial training, I was transferred to the Easthouses Colliery which was close by, less than two miles from Newtongrange. However, the day release class with Mr. Mabon continued so that we worked 4 days at the colliery and one day release on mining engineering theory. As before, I don’t recall the actual orientation procedure that we received on our first days at the mine, but I do vividly recall seeing the cars, known as bogies, for the first time that we rode down the drift incline to the pit bottom. Easthouses was a drift mine, which means that coal seams were reached by a sloped roadway from the surface, unlike all the other collieries in the Midlothian Coalfield, southeast of Edinburgh, which used vertical shafts. This was because Easthouses sat on sloping terrain which meant that a drift incline was more efficient than a shaft. That first day when I walked into the pit head building, I saw the bogies filled with men coming off the nightshift, emerging from the tunnel, each bogie linked together with a huge, thick steel rope creating a train formation. When the train came to a halt the men, still in coveralls and hardhats, rushed off in a single mass heading for the showers.

As soon as all the bogies were cleared, we were given the signal to board. The bogies were long-low open carriages with lines of benches, one behind the other with, and I’m guessing after all these years, twenty rows of four across on each vehicle. What was odd about them was the angle the seats were set at, with a seatback of about 4 inches high, which meant that with the train sitting at the pit head, the slope wasn’t as steep as the actual tunnel, so you were forced to sit on the front edge of the seat. However, when the train moved forward into the tunnel it would dip suddenly to a level that allowed you to sit back on the seat comfortably and begin the descent. The train would move smoothly and quite quickly on its 6 to 8-minute journey to the pit bottom, occasionally having to make a stop for one reason or another. When this happened, it wouldn’t stop immediately, but rather after an initial sudden jolt, it would continue down for a few more feet and then bounce back up again a few feet repeating this up and down motion until the bounce diminished and you realized that you were bouncing as the rope stretched and then receded until it stopped. The first few times this happened was very alarming and you became suddenly aware that the only thing between you and almost certain death was the rope from the pithead that the bogies were secured to, and it wasn’t difficult to believe that it could snap.

When you reached the pit bottom, you’d most often embark on a long hike to the coal face where all the coal-cutting machinery operated. I had been teamed up with a Polish engineer called Alex Wolszczynski who was obviously a fine and highly regarded engineer but who sadly had no sense of humor. However, he was a good teacher and also a very patient and good-hearted man. I remember one morning in particular him stopping en route to the coal face to check on an air-compressor and explaining to me the concept of the machine, how it worked and what problems it was most often afflicted with. There were similar occasions involving pumps, generators and, of course, the various models of coal-cutting equipment at the different coal faces. Along one side of most of the main roads from the pit bottom there would be a conveyor belt carrying coal from the respective faces to the pit bottom where it was wound up the drift incline to the surface and transported by an endless rope system in coal-hutches to the Lady Victoria Center at Newtongrange for screening and washing.

Occasionally, at the end of shift periods you would see miners riding on the conveyor belts to the pit bottom to catch the bogie train to the surface. Aside from saving some already depleted energy, this option would allow them to avoid walking on very uneven road surfaces. Back then it was illegal in Scotland to ride any conveyor belt unless pit management had applied for and been granted an exemption from the Mines Inspector, and in order for this to happen certain conditions had to be met. Where riding belts was permitted, you had to lay down facing the direction of travel and there had to be “a break of minerals”, i.e. coal, “of 36 feet in front and behind the rear of the person man-riding.” Back then us kids had no idea there were all these rules. We’d been told riding the belts was illegal and not much else. In any event, this practice was one that new apprentices could hardly have been expected to resist and, not surprisingly, I had to have a go. One evening after work I was walking back alone from the coal face as my journeyman had stayed on to finish some repairs since apprentices were not allowed overtime. Anyway, there was no one else around and there wasn’t much coal on the belt as the day shift had ended and the night crew hadn’t yet started. I saw my chance and jumped onto the slowly moving belt, sat down and made myself comfortable. (I hadn’t heard about any “lying down” rules.) As you travelled along those roads it wasn’t unusual for earth settlement above to cause some movement in the tunnel which might result in rockfalls, or support beams or other materials protruding into the tunnel. The belt was transporting me along the tunnel perfectly smoothly when I noticed something hanging down from the ceiling and to avoid it, I was going to have to either duck or move to the side or both to avoid my helmet light hitting it. I decided that to employ both of these measures simultaneously would ensure that there would be no collision and, as I did this, I suddenly felt something pierce my left hip and immediately a searing pain. What I hadn’t noticed as I concentrated on protecting my helmet was the fragment of steel girder sticking out of the wall on the left side of the conveyor belt. I looked down and immediately saw that I was bleeding quite heavily. My first thought was to get off that belt before anyone saw me riding it. To avoid getting into any trouble I was going to have to come up with a plausible story to tell the nurse at the pithead. I started walking towards the pit bottom having stuffed my wound with a hankie and buttoned up my coveralls so no one could see the blood. I didn’t want to attract any attention or have to answer any awkward questions. I rode the bogie to the surface without incident and went straight to the infirmary where the nurse cleaned and dressed the wound and gave me a tetanus jab. She asked quite casually if I’d been riding the belt and I denied it profusely, saying that I’d been walking along the road and hadn’t noticed a broken steel girder sticking out of the wall and I’d walked into it. She obviously didn’t believe a word of it and grinning broadly, just said “OK, off you go!”.

Images.

(1) Lady Victoria Colliery, Newtongrange, Midlothian, Scotland. (2) Davy Safety Lamp for use in flammable atmospheres, invented in 1815 by Sir Humphrey Davey. (3) Lady Victoria Colliery pit-head, Newtongrange. (4) BBC 1950s Radio Round The Horne Cast, Hugh Paddick, Kenneth Williams, Kenneth Horne, Betty Marsden & Bernard Breslaw. (5) Round The Horne alternate cast. (6) Memorial Stone dedicated to miners who died at Easthouses drift mine in the early 1960s.