Out of the Camp Ch. 35 – “How would you feel if it were true?”

The week following our trip to Grantham when my uncle had ‘spilled the beans’ about my origins, Mary and I were back on the motorway again heading north, this time to confront my aunt, aka, my alleged biological mother. It was a Friday evening probably a little after seven when we arrived at the house and rang the doorbell. There was a brief pause while we waited then my Uncle Russ opened the door and was more than surprised to see us. He blurted out, “What the bloody ‘ell are you doin’ ‘ere?” He obviously spoke in shock as there wasn’t a trace of hostility in his voice. Actually, I don’t think my Uncle Russ had a hostile bone in his body. He was a sweet, easy-going man who seemed permanently laid back and to me always seemed to be happy, but was always very quiet. I never once saw him lose his temper. He worked as the grounds-man at the Miners’ Welfare Institute maintaining the bowling green, cricket pitch and other sports amenities. In response to his question, Mary said something to the effect that, “We found out about Roger!” Surprised by this, he took a couple of steps back, obviously in no doubt about what we were referring to and quickly responded, “Rose isn’t here. She’s at t’ ‘Stute, playing Bingo.” For those unfamiliar with the East Midlands dialect, the word, ‘the’, is frequently shortened to t’, and ‘’Stute’ is an abbreviation of Institute. So, in this case, “t Stute” is short for “the Institute”. Anyway, this entire exchange took place on the doorstep and didn’t last more than about three or four minutes. He asked if I knew the way, which I did from numerous visits to the village over the years and we got back in the car, drove to “t’ stute” and walked in about ten minutes later.

As we approached the main hall, we heard the Bingo caller and as we pushed open the doors, we saw several tables occupied by about 40 people mostly women, all with their eyes down and focused on their Bingo cards as the numbers were called. When the winning number came up and everything stopped for a minute, all eyes suddenly appeared to be on us and there was a momentary hush followed by a shriek, my aunt leaping up from amongst the crowd and almost echoing my uncle, “What the ‘ell are you doin’ ‘ere?” as she left her table and headed over to us. We went outside and told her about our visit to Grantham the previous weekend, and our conversation with my Uncle George. She immediately broke down, started to cry saying, “I didn’t want to do it. They made me.” As we reached the car park she grabbed and hugged me, kissing my cheeks, saying “I knew you’d find out one day.” At this point, Mary said, “Come on, let’s go back to the house and we can talk”, which we did. I can’t after all this time recall whether we put the kettle on or whether a couple of bottles were opened. Either way when we were settled, Rose had already started to explain that my grandmother, who was on the St. Anne’s Church Women’s Guild, was more worried about the disgrace that would be brought upon the family than anything else if it were ever discovered that Rose was pregnant and unmarried.

She was therefore sent off to a mother and baby home in North Wales to give birth. After a few days, my grandmother and adoptive mother-to-be, showed up unannounced at the home to collect the baby and take it to its new home in Scotland. Rose, understandably, was near hysterical at this development and protested loudly and vigorously but to no avail. A supervisor in the home advised her that this was the wisest thing that she could do under the circumstances. She feared my grandmother’s wrath so much that she acceded to her demands, also signing the necessary papers authorizing the release. Surprisingly, she didn’t speak much about the role of my mother-to-be during this visit. As they were leaving, my grandmother left a parcel containing Rose’s WRAF uniform and telling her to wear it when she returned home so that people will think she’s just been demobbed from the service and won’t question her absence. She had been a telegrapher in the Women’s Royal Air Force and had left on maternity leave earlier.

She confirmed what my mother had told me when I was nine, that my father was French Canadian, stationed in England during the war and had been a pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force. I said that she had also told me he’d been killed. At this, Rose pulled a face and responded with incredulity “No he wasn’t, and nobody told her that. He probably went home, got married and had a family.” I asked her what his name was, and she said she didn’t want to tell me because if Helen ever found out, “there’d be Hell to pay.” Apparently, before Rose gave Helen permission to adopt me, my grandmother had made a trip to the European Canadian Military Head Quarters (CMHQ) in London in an attempt to contact my biological father. Apparently, she’d read or heard that the CMHQ was coordinating the return of Canadian service personnel from Europe many of them with new brides and children. Naturally, the Canadian Government weren’t about to give out personal details of their military personnel but informed her that she was welcome to write to him care of the London office and that they would forward any correspondence on to him. I’ve no idea if my grandmother or, indeed, Rose ever followed up. So that was basically it. My parents returned to Edinburgh and moved in with my grandmother who lived at Bridge Street Lane in Portobello. Years later I heard that I’d been adopted both under Scottish and English law which might suggest, if one were of a suspicious bent, a degree of insecurity over the entire arrangement. This may have something to do with the way the transfer was carried out; simply by having the birth mother sign over guardianship with no attached recognized legal instrument and without the involvement of a legal representative, I really don’t know but, on reflection, the way it was handled does seem a bit sketchy. Apparently, Rose chose my name and, surprisingly, Helen agreed to keep it. It’s been suggested to me that so soon after the end of the war there may well have been some corner-cutting, with Social Services overwhelmed with ‘War Baby’ cases as they were, that in-family adoptions may have been rubber-stamped without following standard screening procedures over the suitability of prospective, adoptive parents. As I mentioned, they were essentially homeless and went to stay with my paternal grandmother. In today’s world I feel fairly sure that the disclosure of that fact alone would end any further discussion until a change took place in the family’s circumstances.

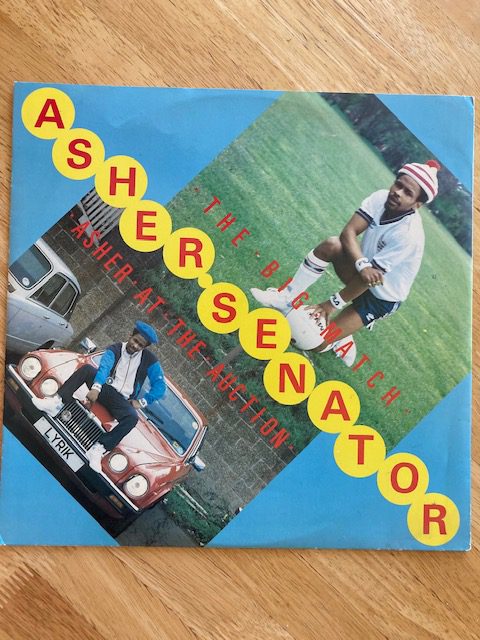

One of the rock groups I’d forgotten to mention earlier was Babuluma who we had signed for publishing, and one afternoon Tony and I were heading to a studio in Camberwell to have them demo four of their songs. We’d just crossed the Westminster Bridge and were driving along St. George’s Road onto the Elephant & Castle Roundabout when, suddenly there was a car alongside honking like crazy and these two guys inside were waving at us and yelling something. I rolled down the window and as the traffic slowed, I was about to level a mouthful of colorful abuse at them when the passenger asked us to pull over because they wanted to take a picture of the car. They were both smiling, and Tony and I were both intrigued. We got off the roundabout onto the Walworth Road and pulled over a couple of hundred yards down the road. We all got out and it turned out that one of the guys was a musician called Asher Senator and the other I think was his manager. They explained that they were recording a 12” dance mix for release on an independent label and they’d love to have my car on the cover, showing the LYRIK’ license plate, with Asher sitting on the bonnet (hood), if I wouldn’t mind. What a cheek! Anyway, they turned out to be nice guys, so I agreed. They were both thrilled and directed us to a car park nearby where we took the shot. The manager-guy actually had a nice-looking camera with him which was lucky as, back then in the dark ages before smart phones, people normally didn’t carry cameras around.

I didn’t find out ‘til later when they sent me copies of the record that the title of one of the numbers was ‘Asher At The Auction’. There was some real irony there as, first of all, that car wasn’t bought at any auction, it was brand spanking new and bought just a few months earlier from a Jaguar dealer on the Western Avenue in Perivale. I’d recently been meeting with our firm of CAs on the Aldwych for our third quarterly review of accounts three months prior to the company’s year-end, when they told me I’d better lose some of those profits or I’ll be paying a fortune in taxes. Roy, my CA, said, “Why don’t you go out and buy yourself a nice car?” Those

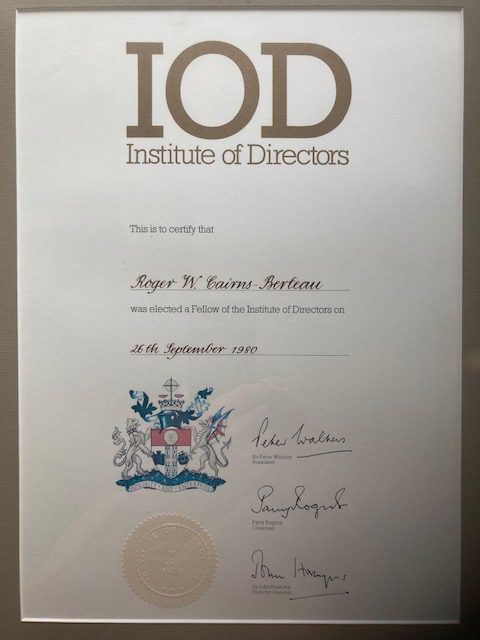

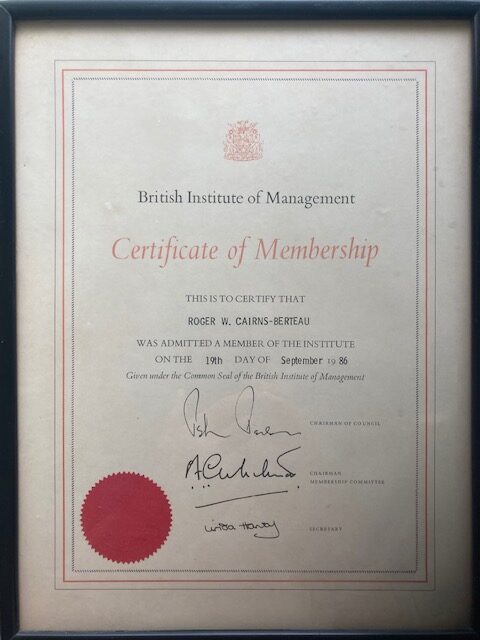

are some very strange words for a working-class kid from a council estate in Scotland to hear, coming from a financial professional in the City of London. It was a very surreal moment and I remember to this day trying to process this, trying to get my head around it. You know that old chestnut, ‘If it seems too good to be true, etc., etc.’ Well, I think in life I’ve been able to cultivate a healthy or unhealthy degree of skepticism, depending on your outlook, but this was the real deal, and I very quickly managed to pull myself together, came to terms with the situation, went out and bought my first, and I think probably my last, brand new car. So, Ashley Senator got to sit on the hood on his record cover and you can see the picture further on below somewhere. The car was a red, 12-cylinder, 5.3 litre Jaguar XJ12 saloon. In the picture you can see the Radioman sticker in the top, right corner of the windshield and, on the grill on the left is my Institute of Directors badge. I was very proud at the time of having been accepted as a member of the UK’s most influential business management organization. Even more so, a year or two later when, unexpectedly, I received a package containing a congratulatory letter from the Director General on my elevation to ‘Fellow’ of the Institute with permission to use the post-nominal (FIoD), a certificate commemorating the nomination, and the car badge. At the time I was truly amazed by this as I hadn’t sought it, in fact, until that moment I was completely unaware of the ‘Fellow’ level of membership. I’m pleased to say that I remain a Fellow of the Institute to this day, in addition to my ongoing membership of the British Institute of Management, now the Chartered Management Institute (MCMI), both of which I joined around the same time in the early 80s.

In any event and getting back to Babuluma, and following the spontaneous Elephant & Castle photo shoot, we continued on to the Camberwell studio where the band were waiting for us and already set up and ready to go with the session. From what I remember, everything went well, and we ended up with some nice tracks for Tony and Steve to shop around record labels. Unfortunately, I now have no recollection of how any of their efforts in that regard faired which is probably not good.

Images.

(1) 1950s Portobello Beach. (2) Bath Street, Portobello early 1900s. (3) Elephant & Castle Roundabout, London. Early 80s. (4) Tony Baggett. Mid 1980s. (5) Steve Thomson with an entry-level staffer, mid 1980s. (6) Institute of Directors HQ, Pall Mall, London. (7) IOD Membership Certificate. (8) Chartered Management Institute (formerly British Management Institute), London. (9) BMI Membership Certificate.