Out of the Camp Ch. 19 – Soviets in London

The first couple of years back in London were largely Soviet influenced and drew us into a strange world of intrigue and suspicion-laden anxiety. During the course of her Russian studies at Hammersmith College, Mary learned of an exchange programme that had existed for some years between the college (now a campus of the University of West London) and Moscow State University, and within a month or two the latest group of students would be arriving from Moscow, and a welcoming celebration was to be scheduled for them. I had no plan or expectation to attend since I wasn’t participating in the class but, when the day came, it turned out that as the spouse of a class member, I had been invited and Mary was quite insistent that I should attend to provide her with some moral support. In the event, it turned out to be a fairly modest affair with soft drinks, sandwiches, crisps and biscuits. There were around 20-25 students I think and 3 or 4 professors in addition to Irina; I can’t remember exactly. Initially, the affair felt terribly awkward and wooden with everyone clustered around the room in small groups conducting themselves excessively formally and unsure, I supposed, of the expected and appropriate British social norms in such a setting.

The evening passed fairly uneventfully and, while speaking with Irina a day or so after the event, Mary had convinced her to invite the students to our home the following weekend for a party which she promised would prove to be a much more relaxed and enjoyable time with some decent food, adult beverages and, of course, modern western music. It so happened that, coincidentally, a neighbor, Sam, had already set that date for a party at her home and so, adding the students and college staff to neighbors and friends she had already invited, we decided to open up both homes to accommodate everyone. In fact, on the evening of said soirée there must have been close to forty people attending and as it was a warm, balmy evening many were relaxing outside or dancing in the gardens. It turned out to be a great success and people were relaxed and really enjoying themselves, even those engaged in political or ideological conversations were conducting themselves in a sober and scholarly fashion. There were two or three girls in particular who I recall clearly held some form of leadership status within the group and were very protective of their beloved Mother Russia. They were utterly convinced of the superiority of the Soviet system of government, thought capitalism eminently evil, and were genuinely puzzled that people in the West appeared happy with their lot. I understood from Irina that in order to be considered for the trip, students were vetted by party officials back home at the University prior to being given permission to travel overseas.

At a certain point in the evening, I realized that I hadn’t seen Mary for some time and wandered around looking for her. I looked in the back garden where the kids were playing. Sam, and Dave her husband, had two boys and an older teenage girl, and they were there with our three along with some of the other neighborhood kids, but there was no sign of Mary. I wandered back next door to our home which had become quiet with no one around except Mary and one of the students sitting in a corner of our living room deep in conversation. When they saw me come in, I thought I detected a perceptible, momentary awkwardness which immediately evaporated when Mary introduced me to Masha. Masha smiled at me and we exchanged greetings, then without hesitation Mary announced, “Masha doesn’t want to go back!” There was a strained silence, and I could feel Masha’s eyes on me waiting for a reaction. I think I babbled at first, not knowing quite what to say. Actually, to be perfectly honest, I had no idea what to say. I think I asked what she meant. “Masha doesn’t want to go back to Russia”, Mary reiterated. For those of you not around during the Soviet era, or who are too young to remember it, this was the stuff of a le Carré novel and didn’t happen to people in real life. The Soviet Union was generally perceived as a sinister, closed society to anyone from outside, shrouded in mystery and generally regarded, as President Regan suggested in his 1983 Florida speech, as the Evil Empire. Until these recent developments, nobody I knew had ever been there and no one they knew, to my knowledge, had been there either.

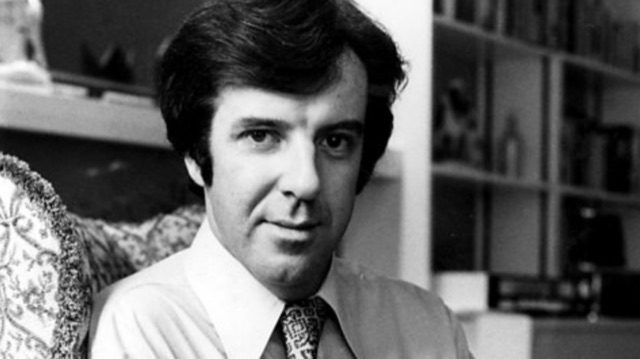

We continued talking for some time, trying to work out how we could help Masha and quickly decided that we needed to speak with Irina. At this point some of the crowd started drifting back to the house and it was necessary to quickly change the subject. Later that evening when the students had left, we had an opportunity to speak with Irina and, with Masha’s prior permission, discussed her situation. It transpired that Irina had a friend who lived in Earl’s Court, was a freelance journalist covering Eastern Europe for a number of prominent publications and had many political contacts. It was too late in the evening to call her and so Irina promised to do that the following day and let us know what she said. She was as good as her word and a couple of evenings later, Mary, Masha and I headed to Earl’s Court to meet the journalist whose name was Lillian. She lived in a ground floor flat in Bolton Gardens which was a huge coincidence because about 8—9 years earlier I had installed a TV aerial for Russell Harty the late ITV presenter and chat show host who lived in a basement flat there.

Lillian’s flat was in disarray due to some decorating and structural work that was clearly underway. However, there were books and newspapers also strewn all over the place and we had to clear chairs to find somewhere to sit. Lillian was very welcoming if a little distracted, but the chaos didn’t seem to trouble her at all. As she had already spoken to Irina, she had a good understanding of the situation but asked for clarification on certain points, some information on Masha’s background, where she grew up, what her parents did and did they know what she was planning (they didn’t, of course!) and at what point had she decided that she wanted to stay in the UK. She also asked if we had discussed how we proposed to pull this off. We had and it was decided that Masha would stay with us until we could secure political asylum for her. Between the time of her voluntary ‘disappearance’ from her group and her securing protection under British law, she would be considered ‘Stateless’ and therefore vulnerable to kidnapping by Soviet Authorities in the UK and removal from the country, and there would be nothing we or the UK government could do about it. While we were there Lillian made a phone call to someone who she said dealt with this kind of thing on a regular basis and that he would know what to do. From what she said we guessed that he worked for the government in some capacity, but it wasn’t clear at which department.

In the meantime, she said we need to discuss how Masha planned to disappear. Masha explained that she was sharing a room in a family home with two other fellow students and that they normally would travel together to class each morning. She said that she could simply feign an illness one morning, stay in bed until the other students had gone and then pack, get dressed and make her way to our home which was a 15-20 minute walk from where she was staying. This then was our scheme and when we left Lillian that evening, she said that we should move quickly and let her know when we planned to do this. She would then immediately convey the details to her contact who in turn would submit a request for Masha to be granted an interview with government immigration authorities. Hopefully, this would lead to her being granted political asylum in the United Kingdom. Permanent residency albeit the ultimate goal was, at this stage, a distant dream.

The following evening Irina came over with Dima who’d been kept abreast of developments and had decided on learning of our discussions that he would insist on speaking privately with Masha before we took another step. Soon after they arrived Dima and Masha went into our bedroom together and closed the door. Irina seemed unperturbed by this development as I think that Dima had likely revealed his intention to do this before they arrived. When they emerged from the room, there was a tenseness between them both and I sensed it was entirely due to the gravity of the situation about to unfold. They were in there for perhaps 30 minutes, and we could clearly hear them talking. At one point Masha sounded as though she was weeping softly but it was difficult to be sure. When they came out it was clear she’d been crying, and Dima looked tense and very serious. There was an awkward atmosphere which Mary, in her inimitable way, shattered by suggesting we all have a drink. We spent a couple of hours talking about the plan and Dima, who’d made his earlier skepticism plain, was suitably mollified after hearing Masha elaborate on her clear understanding of what she was embarking upon and the inherent, significant risks involved to both herself and her family. Nonetheless, Mary added, and I reinforced this, that it wasn’t too late to change her mind if she was having the slightest doubt, that whatever she decided, we would support her one hundred percent. At this, Masha broke down, dashed across the room and hugged us both all the while reassuring us that she didn’t feel pressured either way but that she was certain that she wanted to go ahead.

I found out later that the following morning Irina and Masha had made a trip to YMCA Press, a bookshop in Pimlico, to meet Lillian and the journalist with whom they’d spoken earlier, in addition to two other women who had themselves defected from the Soviet Union. A day or so after this meeting Masha told us that many people involved with immigration and defections met regularly to update each other on recent developments and incidents; a sort of jungle telegraph for lost souls in the West. The YMCA Press, a publishing house established as Editeurs Réunis was set up in Russia in 1900 to provide education, religious and philanthropic programs”, and was also a major distributor of Samizdat Literature, this was a form of illicit material including books, pamphlets and reports published during the Soviet era that were critical of the regime. Anyone in the Soviet Union found in possession of such items would face severe punishment which invariably would involve incarceration or worse.

There followed a few anxious days of frantic activity, with urgent phone calls from various concerned parties. Mary had also done some shopping to help mitigate any sense of the gulag lest Masha be stuck with us for longer than she anticipated. She bought some toiletries, towels and bed linen, and had set up a vase of fresh cut flowers by Masha’s window. On the day in question Mary had decided to take a day off work to be at home when Masha arrived and help her get settled into the room we had prepared for her. The night before the big day, Irina and Dima came over to learn about the most recent developments and discuss, in particular and in relation to Irina, the reaction of the college when it was discovered that Masha was missing. As far as Irina knew it hadn’t happened before and certainly not in her time at the college. Despite this she was surprisingly calm and unperturbed by was about to take place.

The following morning, we were up and about and waiting for news or simply the imminent arrival of Masha at our front door and wondering what kind of an anxious state she might be in. We didn’t have long to wait. Masha arrived with her suitcase looking surprisingly fresh and prepared for whatever the day might throw at her. Now the waiting began…

Images.

(1) Russian Embassy, Kensington Palace Gardens, London. (2) Russian Hammer & Sickle National Flag. (3) Russell Harty, TV Presenter. (4) Moscow State University.