Out of the Camp Ch. 34 – Sunday Mornings in Moredun

Before I get back to Moredun I need to finish this story referred briefly to in OotC – 22.

“Ten days later he was gone. Irina told us that he’d received a late-night phone call from the police in Genoa where there was a problem with the truck containing his equipment and that this had delayed the ship’s departure to Jeddah. Dima had dropped everything, jumped into his car and took off for the 15-hour drive from Ealing, West London to the Italian port. It was a long story – for another time – involving the Carabinieri, drugs and a police dog who couldn’t find any drugs.”

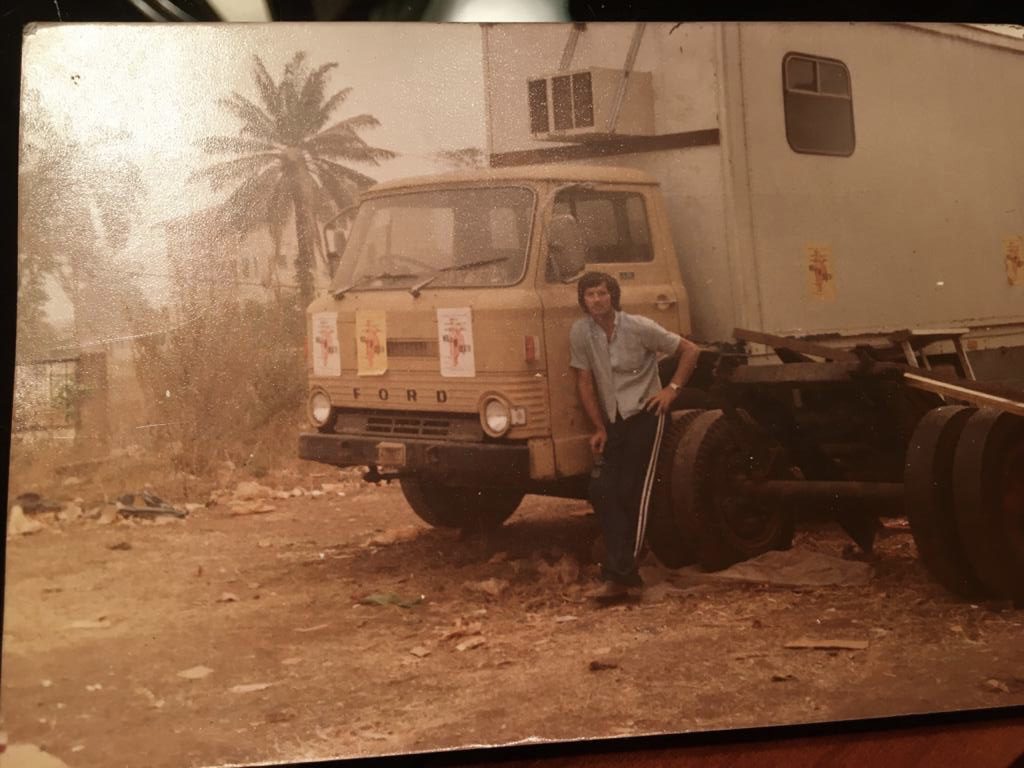

Since I posted that, Dima was in touch and filled me in on the episode which took place in Genoa when the ship carrying his equipment from Lagos to Jeddah had made a fuel stop there. He first heard that there was a problem when he was at home in Ealing, waiting for the ship to arrive in Jeddah. He received a call from the shipping agent telling him that his truck couldn’t be loaded onto the vessel because of some mechanical problem in addition to gasoline leaking from the trailer. There was no mention of why the vehicle had been taken off the ship in the first place if it was there simply to refuel, however all will be revealed in due course. He soon found out that this story was simply a prevarication used to entice him to Genoa for another reason. It seems that an Australian wall of death rider called Peter Catchpole who lived in Liverpool, on discovering that Dima – or at least, his equipment – was en route to Jeddah, had called Interpol and accused him of being a drugs dealer masquerading as a wall of death rider. Catchpole had done this because, according to Dima, they’d had a business deal that had gone bad, and Catchpole blamed Dima for this and wanted to get even.

When Dima arrived at the port gates, he asked the security guard how he could gain access and the official had told him to wait, and went to place a call. Within 5 minutes, a squad of approximately twenty-five Carabinieri arrived, slapped him in handcuffs and drove him to his truck/trailer. When they arrived several of them, speaking perfect English, explained that “life can sometimes be difficult but together, WE can make it less troublesome.” He told me that he could understand every single word that they were saying to him but, nonetheless, he didn’t know what they were talking about. After going over this several times, “again and again they told me that this is my last chance. I told them I don’t know what you mean. I really don’t understand any of this.”

“OK, man. Enough is enough!” They told him that, from now on, he’d made his life very difficult, and that everything will be in writing.

“This is your stuff?” – “Yes!”

“Did you load the truck yourself?” – “Yes!”

“Did anyone else have access to your equipment?” – “No!”

“Do you use drugs?” – “No!”

The Customs Declaration and Authorization was signed, and they opened the truck. Three Carabinieri led him inside still in handcuffs. After a short wait, a small truck arrived with a cute little dog inside, and her handler helped lift her into the truck. The dog started running around “as though someone had stuck a sharp nail in her ass.” The handler kept saying something in Italian like “go on, good girl, bravo!” Within five minutes or less, the dog “with a guilty face was trying to jump out of the truck.” At this point a senior officer approached Dima and removed the handcuffs. Then, the dog handler spoke to the officer and “a very intensive discussion began!” Dima described the situation saying, “Picture this! Approximately twenty Italian policemen deep in heated, animated discussion – in Italian, of course – looking across at me from time to time, clearly disagreeing about something.” They then walked over to him, declaring that it was lunchtime and invited him to join them in a nearby café. He said, “I can’t! I need to change money. Broadly smiling, they told me that I am their guest.”

After lunch, which was served with red wine, they returned to the truck and “all twenty faces become grim again and the top man said, ‘We are the best drugs team in Italy! We’ve traveled here from all over Italy to get you because we believe you are a leading drug dealer! Our dog, Lucy, is the best one in Italy!’ I said, ‘Very good, and I have nothing against your dog!’” At this point the dog handler came over near to tears. “Roger, this man is standing in front of me pleading, saying that Lucy is in a terrible state, she is in deep stress and this result could endanger the future of the narcotics unit. I told them, ‘Come on, guys. What can I do? Am I a free man? Can I go to finish my business?’ Now the dog man approached me and asked me to do him a great favour. Would I allow him to place real drugs in my truck so Lucy can have another go? Against my better judgement, I said ‘Go on!’ Within a couple of minutes, a car pulled up and a man carrying small packets got out. He went to the truck, opened one of the tool-boxes and put the packs inside. The truck gate was closed, and the handler came back with Lucy, gave her some instruction, opened the gate, lifted her and she went in. Within ten seconds she was scratching furiously at my toolbox, screaming and screaming! Every man in the team stroked her and the dog man started kissing her. Everyone was happy and I took the opportunity to ask the head agent, ‘favour for favour?’. How did all this get started? He told me that the tip had come from the Merseyside drugs unit in the UK. This unit, naturally, covers Liverpool and the surrounding region, and Peter Catchpole lived there until his death a couple of years ago.

Returning to my childhood in Moredun, I always looked forward to the weekends when my dad would come home from his job at St. Andrews University, not that we would do anything special, although we’d sometimes visit my auntie, his sister in Granton for tea, and she’d always insist that I have at least one cake from every plate on the table. I used to enjoy this not only because I loved her home-made cakes but also because she’d say, “Now don’t look at your mother, you’re at your auntie’s now and you can do as you please.” My mother would never say a word on these occasions. Occasionally, when Hearts were playing at home on his weekend off, he’d take me to Tynecastle to see a game. This didn’t happen very often as his weekends off seldom coincided with a home game. When we did go, he’d sometimes embarrass me when one of the players misjudged a ball and shot it straight up into the air and, whenever this happened, my dad would be the first to yell, “Highest the day!” He did this every time it happened, and I used to cringe because he always said the same thing. It was like he was waiting for it to happen so he could shout it. We’d usually stand behind the away team’s goal to get a good view when (if!) Hearts scored, and I’d always worry that the same people would usually be at that end of the pitch too and if the ball went up, they’d hear him every time he yelled “Highest the day!”

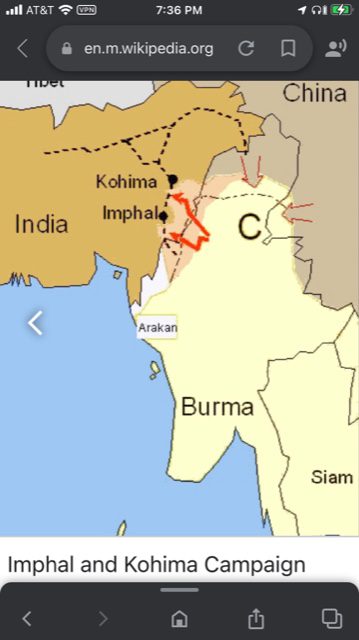

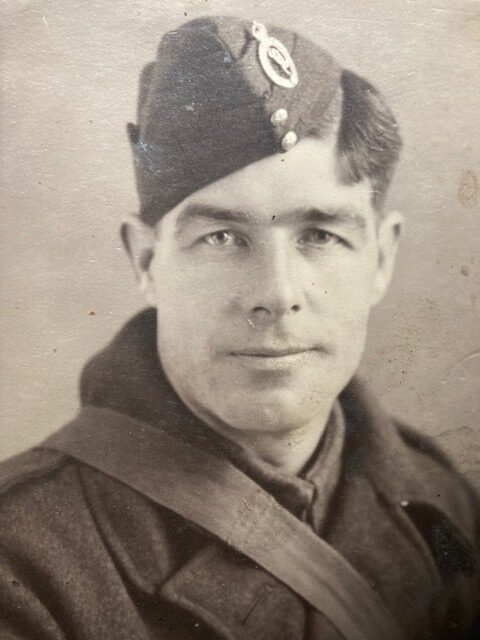

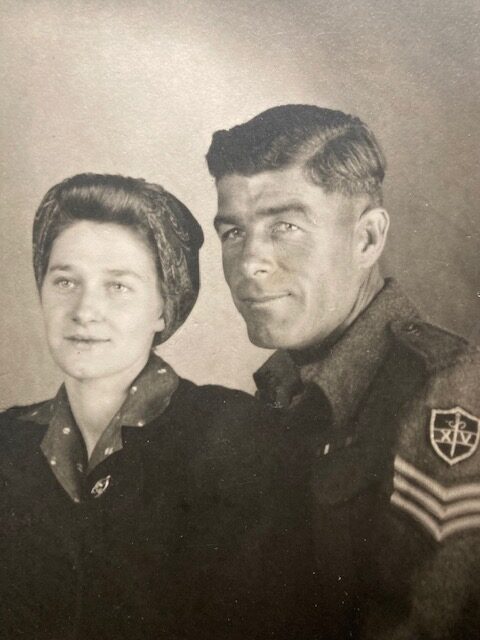

Everybody liked my dad; he loved to laugh and would really enjoy a good joke. Whenever he went to the shops, he’d talk to everybody and would take much longer to do things because he’d get into conversations with complete strangers. He could be very stubborn at times, especially when it came to politics. We didn’t go to the pictures very often but when we did it was usually to see a comedy and when something funny happened my dad’s laughter could be heard throughout the whole theatre. My mother hated it and would nudge him in the ribs and tell him to stop but he usually didn’t because everybody else was laughing. He just happened to be the loudest laugher – if that’s a word! I think the happiest time of his life was when he was serving in the army in India and Burma, both before and during the war. He was overseas for more than ten years with just one leave of absence for a visit home by sea. Initially, he was in the KOSBs (King’s Own Scottish Borderers) and later, the Royal Signals. When I was growing up, he would often refer to India or Burma along the lines of, “when I was in India/Burma, etc. etc.” He’d talk about everyday things or memories he’d have about life there, or food but like most veterans of World War II, he never talked about the actual war or about any action they saw and were a part of. Before my kids came along and he really began to open up about it, the only reference I ever remember him making, was when he talked about being in Elephant Bill’s 14th Army, often referred to as the ‘Forgotten Army’ in the Burma Campaign because it was largely overlooked and remained obscure until long after the war.

The one thing I dreaded when my dad came home from St. Andrews for the weekend were Saturday nights (sometimes), and Sunday mornings, especially Sunday mornings! In the last episode, I made a cryptic reference to certain personal childhood experiences that I was considering sharing but, concerned over how some might react, I paused and sought some professional help. I was encouraged unreservedly to go ahead and publish as it was more likely that someone might be helped by this rather than hurt by it. If some were offended, that would be unfortunate, but they’d get over it. Saturday night at the Robin’s Nest pub was Whist Drive Night, and when my dad was home, my parents would generally go to it and leave me alone in the house. I’d be anywhere between seven and ten years old at the time. I remember that I didn’t mind this at first. By ”at first”, I mean in the early evening when they’d first leave the house, but as the night drew on, I began to panic and my imagination would kick in, and I’d envisage all kinds of dreadful things that might have happened to them and so what would I do? I’d lie in bed screaming and crying in terror wondering what was going to happen to me. I think the next thing I knew it was morning and they were home, and I was alright.

Except that it was Sunday morning and Sunday mornings were the time I dreaded most. The walls in a prefab are famously paper-thin and totally absent of any sound-insulating properties. I don’t understand now why this upset me so much because I really didn’t understand what was going on but, whatever it was, I really hated it and couldn’t wait for it to stop. Through my bedroom wall from my parent’s room next door, my father would be pleading and begging gently, and my mother would be crying saying, “No! No! Please, no! This would go on for ages and I’d dive under the covers and stick my fingers in my ears praying for it to stop. Looking back, I now don’t understand why I couldn’t have just got up, got dressed and gone outside. Probably fear of one thing or another. I really don’t know now. As I wrote in the last episode, “I’ll never really know or fully understand the extent to which the challenges she faced as a young girl or later, as a young woman caused her to be so irreversibly damaged. Whatever it was, I feel sure it had a huge effect on her, and likely contributed significantly to her bouts of uncontrollable rage and also, very likely, whatever difficulties she had on those Sunday mornings all those years ago. As I think I alluded to earlier, there were certain things back then, certainly in working-class Scotland and further afield, that just weren’t spoken about. You were expected to just “pull yourself together, shut up and get on with it”, a sort of regional interpretation of the ‘stiff upper lip’ from our cousins to the south. Any thoughts of therapy or, heaven forbid, visiting a psychologist would be regarded as ridiculous because, whatever it was, it was just a part of life, and everyone had to deal with it so what was so special about you. It’s no doubt, pointless to emphasize that my parents are no longer with us nor are any of their respective siblings, so I hope that no one is hurt or offended by what I’ve written or regard any of it as something of a betrayal.

Images.

(1) Dima and his truck. (2) 1930s/40s Burma, now known as Myanmar. (3) My dad’s regiment. He’s standing on the left end of the second line from the front. (4) My Dad in his Royal Signals uniform. (5) My parents in the early 40s. (6) My Dad with his truck. (7) This is a random picture that immediately brought back memories of the Monarchs at Meadowbank Stadium in the early 60s. (p.s. I think this is a current shot at the Berwick speedway.) (8) Insignia of the Royal Signals. (9) Insignia of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers.