Out of the Camp Ch. 32 – Jeddah, Moredun, the Chain Pier & Music

(This continues the story prior to the ‘flashback’ following the Saudi Arabian episode, ‘Out of the Camp–23’)

As Wali drove us back to the hotel from the Sheik’s compound – Dima had left his car there earlier – I was processing the events of the evening and, indeed, the additional other-worldly events of the past week. The bizarre, and ‘dry’, Saudia flight out of London a week ago, the ‘artsy’ roundabouts (traffic circles) I saw on the drive from the airport, the two-floor building with the eight-floor-strong foundation, being repeatedly asked if I was Jordanian, the day-long tour of the Sheik’s projects in a chauffeur-driven stretch limo, our narrow escape from arrest by the Religious Police for eating while strolling on the beach during Ramadan. To this alien world, in addition to sending a bunch of seasoned stunt drivers and motorcyclists, I was also proposing to dispatch a group of teenage skate boarders and BMX bikers and, I don’t know why but, the thought of it took me back to my first bike in Moredun. Granted, I was quite a bit younger than these kids, but they’d be equally, no, more vulnerable, in this setting.

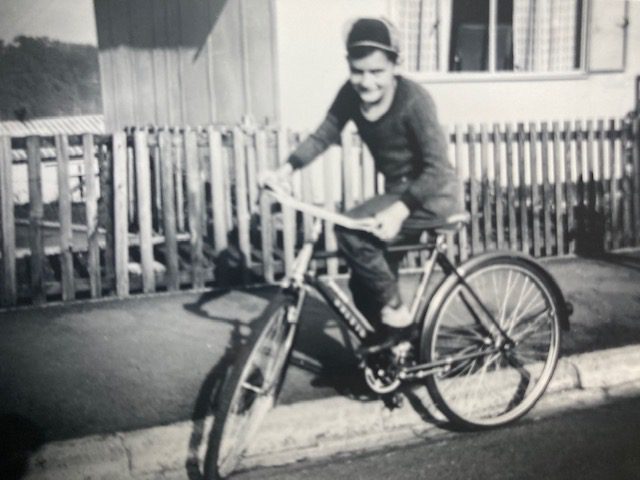

I was terrified of falling off my first bike, a Raleigh 18”-er which I got for Christmas one year. I couldn’t mount it without propping it up with the pedal on the kerb at the top of the slope of our street, Moredun Park Avenue. I’d gingerly get on without disturbing it and then, putting my faith in my feet, I’d push off with the upper pedal and this would launch me freewheeling down a 100-yard stretch of the street to a right-hand corner which began to rise immediately on turning, and thereby slowing me down until I came to a complete stop. Then, as regularly as clockwork, I’d fall over onto the road still astride the bike. This regular occurrence would always take place in the same spot, right outside Mrs. Blackie’s prefab where she, invariably, would be hanging out the window and every single time would yell too late, “Keep pedalling”, and she’d laugh, but not in a cruel way, and then ask me why I stopped pedalling, I’d reply, “I’ll fall off!”. This, naturally, would set her off again giggling, saying, “but you fall off when you don’t pedal. If you keep pedalling you’ll learn to keep your balance and you’ll stop falling over.” The logic of this was too much for me at that point in my life. I knew she was trying to be kind because my mother had told me that Mrs. Blackie was always going on about my lovely curls and wishing her girls’ hair was like mine. I thought there must be something to this because I’d noticed she was always looking at me. Avril, her eldest was very pretty but I don’t remember her younger sister’s name.

My bizarre meanderings were interrupted when the car pulled up at the Albilad Hotel, and Dima and I thanked Wali for the ride back and he wished me a safe trip back to London as he drove off. I said my goodbyes to Dima and he went off to find his car. My flight home was mercifully uneventful partly, I suppose, as I’d managed to get a seat on a British Caledonian flight thereby avoiding the seasonal theatrics observed by Saudia and their passengers also, it didn’t hurt that I was able to enjoy an adult beverage or two.

Back in the office the next day things were buzzing with visas being arranged with the Saudi Consulate for the stunt team, documentation being completed and logged for the bikes and other equipment being shipped to Jeddah within a couple of days. The offshore operation was still in high gear, and I had meetings set up for later in the week in Aberdeen. Prior to this I’d be heading to Edinburgh as Sante Fe International’s ‘Apache’, a brand-new Dynamic Positioning steel pipe laying vessel had just arrived in Leith Harbor, from the Galveston, Texas shipyard, and I’d be meeting with the radio operators we had en route to the vessel before its departure to the Buchan field to lay pipe.

It was always a real pleasure returning ‘home’ to Edinburgh because I’d been away for decades, but my visits were always regrettably short as time was always limited. It might seem odd to still regard it as home after so long but its where for me everything started. Whoever it was who coined the phrase, ‘Absence makes the heart grow fonder’ had been around the block once or twice. I think its more commonly related to people rather than places, but the sentiment holds true equally well in both circumstances. The changes were always surprising, sometimes pleasantly so and equally often, not so much. I really don’t remember what was at the top of Leith Street before the St. James Centre was built but, whatever it was, can’t have been as out place as that edifice. So, I was glad to see it gone but now; Oh, I don’t know! Why can’t the planners aim to create something in keeping with the surrounding architecture. I haven’t been back since the St. James Quarter opened so I guess I shouldn’t say too much until I’ve seen it in the ‘flesh’.

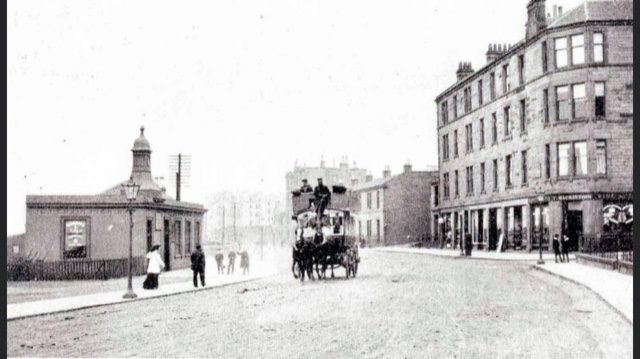

Leith is a different place from the way it was when I was growing up and from what little I’ve seen I like it, but I’ve no idea what the effects of its gentrification have had on the native community. My cousin Jessie used to live in Newhaven, not far from the Royal Yacht, in one of those red stone tenements and she had a nice little flat. She’s gone now so I don’t know if those flats are still there or not. I also recall during our final visits together, her anger over the mess that construction of the tramlines were making of the city, and the seemingly endless chaos she described, was probably the most enduring and emotive of our conversations. That, and the incomprehensible decision all those years ago in the 50s, to tear up the original tram system which had been operating in Edinburgh in one form or another since 1871.

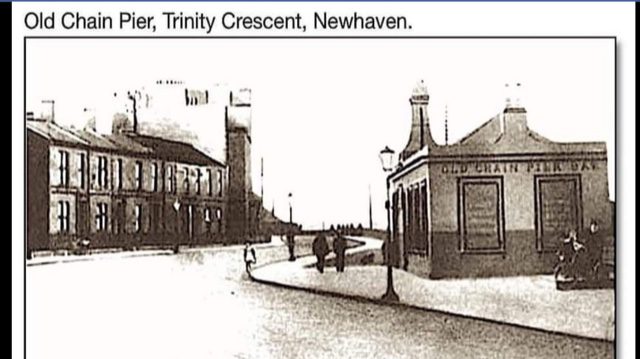

I met our guys at the harbor by the ‘Apache’ following her maiden voyage across the Atlantic newly arrived from the Texas shipyard and looking magnificent. We had lunch at the ‘Old Chain Pier Bar’ and I honestly don’t know how many decades had passed since I was last there but one thing was for sure, I knew Betty would have been long gone by then. She was already an old lady in the 60s when, still wearing her bamboo framed glasses, she’d wield that huge cutlass she kept behind the bar at any customer who got out of hand or gave her any ‘lip’. The entertainment was free and, at 5 feet and not much else, she ruled with an iron rod, and it was always a fun place to hang out.

I don’t remember the first time that Tony Baggett and Steve Thompson showed up at the office. I do know that we were approached about getting involved with a music publishing operation that needed some backing and administrative support. All in the office were aware of my musical aspirations and activities in managing and promoting a Liverpool singer/songwriter called Abraham Ali and so, while I was still in Saudi, they set up an appointment for them to come in and see me. When they showed up, they explained what they were doing and how much they’d accomplished with their company, Wakeagre Limited, but what they needed now was the wherewithal to bring their efforts to fruition. This, clearly, was all very vague and I asked them to spell out why they were here and what they wanted from me. After some minutes of to-and-fro, I gathered that they had a small “stable” of artists and needed the means by which they could package and showcase them. We were making progress, but it was painfully slow, and I had to insist that they get to the point. The bottom line was that they operated like a management company, but management contracts are famously difficult to enforce when an artist is seduced away by a major record label or agency. A way to circumvent such an outcome they explained, is to sign the artist up to a music publishing contract while continuing to function in a management capacity in working to further the artist’s career. In the event that say, a record deal is secured, the publisher’s management activities can continue or, alternatively, the artist may sign up with another manager and the publisher would simply step back and retain music publishing rights. In the ultimate event, that the artist achieves success, the publisher would have the opportunity to recoup their costs and also earn the agreed percentage of publishing royalties. To achieve this end, Tony and Steve needed a reputable music business lawyer to draw up enforceable agreements. When we met, I think they had three groups signed, all of whom wrote their own material. In addition, there were two singer/songwriters who also were interested in working with them but to date in their case, nothing had been signed.

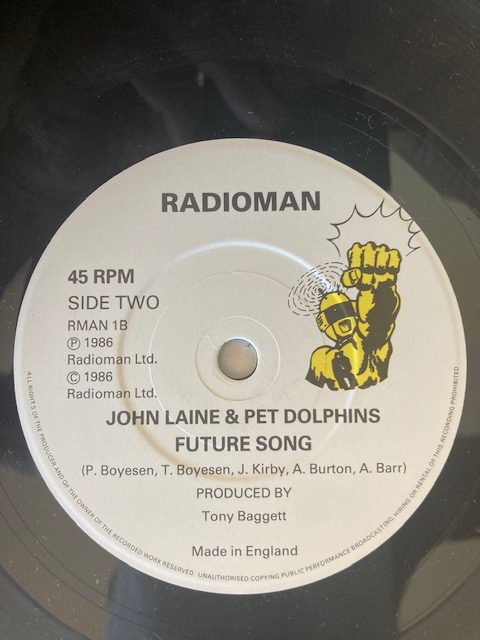

What they needed from me, in addition to access to legal representation, was the means to create marketing materials including time in demo studios, photographers and artists’ biographies, in other words, financial backing! Home studios back then had not yet become commonplace but there were always deals available if you knew who to talk to, same applied for photographers and on the bio front, I felt I could handle it. We didn’t need a literary giant to cover that role. So, what remained was the form the business was to take, were we absorbing/taking over Wakeagre Limited? including assets i.e. existing agreements with signed artists, etc., equity distribution of new company, numbers of voting and non-voting shares, duration of the agreement, and were these two looking to get paid? Negotiations were relatively straightforward, and we quickly reached an understanding. I set up an appointment with our lawyers who we met with within a few days and contracts were signed within the month, and we were set. And the name? Well, the same as everything else, I guess, with “Music” tagged on, viz, ‘Radioman Music’. In the meantime, we had applied for membership of PRS, which is required to receive performance royalty payments, and this took several weeks but eventually was approved. We set aside a small room as an office they could share, and they started showing up for work almost immediately. They brought in the groups that were going to transfer over from Wakeagre Limited, and sign up formally with us and also one of the writers who they worked quite closely with, David Motion.

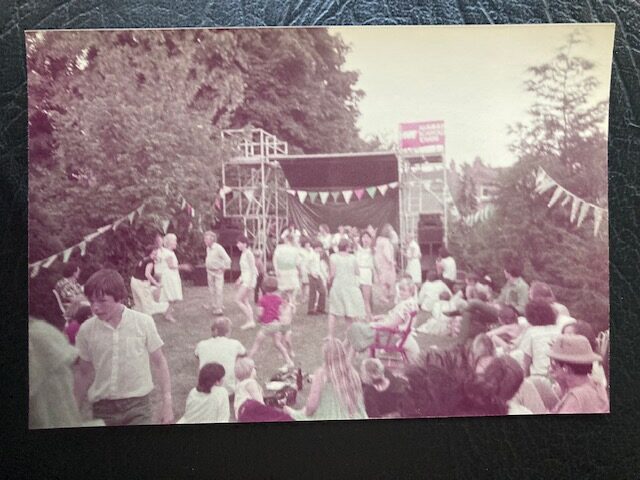

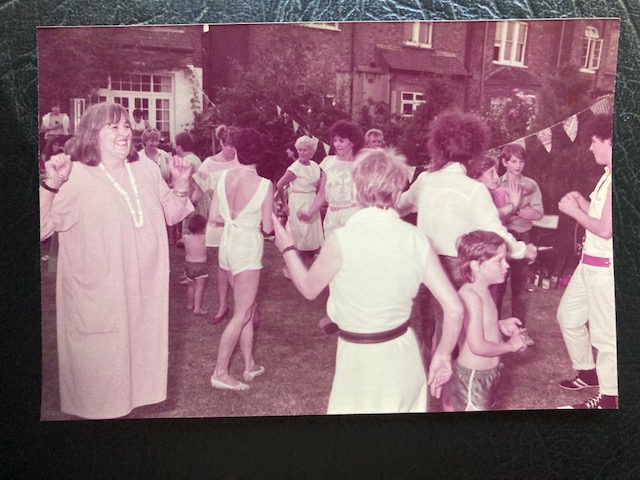

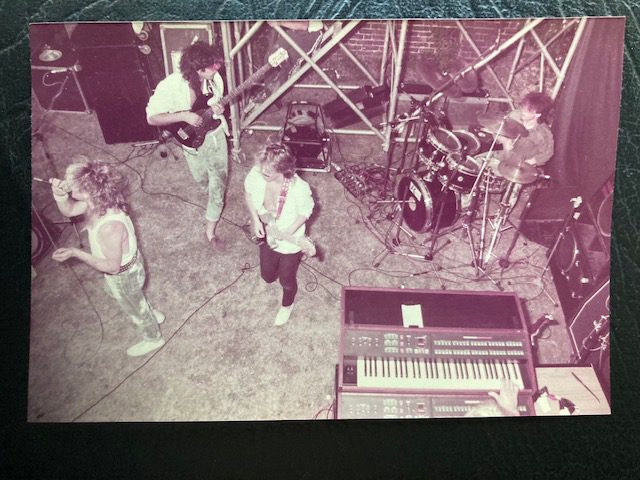

As time passed, we signed up five groups who all wrote their own material, an additional songwriter, David Motion, and another guy, George Webley, who didn’t want to tie himself down but would give us rights to material that we were interested in, a sort of song-by-song option. The groups I remember were, The Cold Pharoes, The Pet Dolphins, Boplicity, Life After and Pleasurama. (Life After is the group featured in the attached photos of a charitable fund raiser we had in our back garden in around 1985.) George Webley, who years later became well known as a BBC Radio London DJ, ‘Big George’, and also a successful composer of TV theme tunes including, ‘Have I Got News For You’, ‘The Office’ and ‘Graham Norton’. Unfortunately for us we didn’t get the option and, consequently, no percentage of any of those royalties. Sadly, George is no longer with us as he died suddenly at age 53 after suffering a heart attack at his Milton Keynes home in 2011.

Boplicity were already on the radar of EMI who wanted to put them in their Manchester Square studio before we’d even signed them. This actually came together but ultimately when it came to taking up the option, the label decided to ‘pass’. At least, we got some decent demos to shop around other companies at no cost to us. Later, Micky Most, the famous record producer expressed interest in The Cold Pharoes and after meeting the band and seeing them at a gig, told us that they were proposing to formalize a verbal offer and would be sending over a contract the following week to sign with RAK records. These are two high points that were the culmination following months of frenetic activity on the part of Tony and Steve, setting up meetings all over town, checking out other groups, endlessly cold-calling record companies. Over time they got to know A&R folks in many major and other labels in town. The RAK contract never arrived and, we learned from them later that they decided to cancel the offer when, unbeknownst to us, the band showed up with their new manager and demanded an increase in the agreed advance. This ‘new manager’ was none other than Bob Curry, an American A&R guy who’d been at EMI when we were talking to them about Boplicity. He’d later been fired by EMI, but nobody would tell us why. In any event, he’d managed to make contact with The Cold Pharoes and convinced them that they could get more money if they renegotiated the RAK contract and they fell for it, forgetting that they’d made a gentleman’s agreement with RAK and shaken hands on it. Tony tried to explain to the label that we had nothing to do with it, which was true, and that we’d spoken with the group, who’d agreed to revert to the original agreement. Not surprisingly, they were no longer interested. I couldn’t blame them. In their position I’d have had a similar response.

Images.

(1) Me on my bike outside the prefab in Moredun. (2) MV Apache. (In the 80s it used to be silver.) (3) Betty Moss, former owner of the Old Chain Pier Bar, Newhaven, Edinburgh. (4) The Old Chain Pier Bar, late 1800s/early 1900s. (5) The Old Chain Pier Bar, 1960s. (6) The Old Chain Pier Bar, 1940s. (7) & (8) Radioman Music – see above. (9) Life After playing at a fund-raiser in our back garden around 1985. (10) Ealing Dyslexia Association fund-raiser in our back garden around 1985. (11) 1985 back-garden fund-raiser. (12) Life After.